Saturday 28 May 2016

Abandoned Money

I read about a third of Money (1984), and found it enjoyable. I wouldn't call it great though, and doubt that I will ever read anything by Martin Amis again. I think Money's problem is that, as Amis has said himself, it is a 'voice novel': almost plotless, a series of debauched anecdotes made entertaining by the amusing narrator-protagonist. However, at 454 pages (I reached page 169), it feels too long a novel to be carried mainly by its voice: I found myself losing interest, thinking Alright, I get it, he drinks a lot and has problems with women, and wants to make lots of money. There are better books out there: I decided to abandon it.

Sunday 22 May 2016

Four Christopher Priest Novels

After owning a copy for over 3 years, and meeting the author 3 times, I have finally got round to reading The Prestige (1995). It is the fourth Priest novel I have read, following The Affirmation (1981), Inverted World (1974), and Fugue for a Darkening Island (1972) - I read these three way back in 2012, so they are not quite fresh in my mind.

|

| Fake cover, featuring Escher's Drawing Hands |

The Affirmation was my first Priest novel, and it remains my favourite. Drawing Hands by M.C. Escher would be a perfect cover image for this novel which contains two parallel stories: one set in 'our' world, the other set in a 'fictional' world. Both protagonists attempt, for differing reasons, to write autobiographies, but end up retelling their life stories in a fictional setting. The two autobiographies/fantasies blend in to each other, and the reader is left wondering which world is supposed to be 'real'. It's a very clever, very artistic mindfuck of a novel. Priest describes it as his 'key' novel: when his writing became obviously unique, Priestian, with its unreliable narrator(s) and narrative shocks.

'This is the book CP regards as his ‘key’ novel: all the novels before it lead towards The Affirmation, none of the ones that follow could have been written without it. It is deceptive in form, not only in the way the protagonist’s story is told, but also in the way it is presented.' (source)

Inverted World is the best of Priest's pre-Affirmation novels, when his work still resembled traditional SF, and has one of the most famous opening lines in all SF:

'I had reached the age of six hundred and fifty miles.'

The characters of Inverted World live in an ever-moving city, fleeing from a destructive gravitational field. In front of the city engineers are constantly placing railway tracks; behind, the old tracks are being pulled up. The protagonist, Helward Mann, comes of age and joins one of city's guilds. Through him we learn about the city and the wider world. Some of the imagery of Inverted World is quite trippy and psychedelic. I remember the second half not being as satisfying as the first, but it is still a very good book and certainly worth reading.

Fugue for a Darkening Island is one of Priest's lesser known works. Events since its publication have made the work appear more sinister than was intended. When first published it received praise for being progressive and anti-racist, but when re-released and re-reviewed a few decades later the same magazines considered it very backwards and racist. The description on Wikipedia certainly makes it sounds like a Daily Mail nightmare:

'First published in 1972, it deals with a man's struggle to protect his family and himself in a near future England ravaged by civil war brought about by the failings of a Conservative government and a massive influx of African refugees.'

Fugue focuses on the changes to the protagonist's character over the course of the disaster by telling the story achronologically. The narrative jumps around between time periods to show us the different 'versions' of the character, contrasting their different perspectives. This novel does not compare well against the other Priest novels I've read: it's a very early work, his second novel, from when he was just starting out as a writer.

And then we come, over 3 years later, to The Prestige, which was made into a film by Christopher Nolan and is therefore Priest's most famous novel.

(Spoiler for the movie ahead)

The action takes place in two time periods: the majority of the book tells the story of a rivalry between two Victorian stage magicians, while the frame-story, narrated by the magicians' grandchildren, explores the legacy of the feud to the present day. This novel is obsessed with doubles, and the very structure of the novel reflects this: each time period gets two narrators, each telling their side of the story.

The book is very different to the movie, which builds up to a Big Reveal where the magicians explain their secrets to each other. A magician never reveals his secrets: there is no Big Reveal in the book.

I'm getting tired, and feel if I write any more about The Prestige I may spoil some of the differences between the book and the movie, or spoil too much of the movie, so I'm going to leave it there. It's a very well constructed novel, still packed with surprises for those who have seen Nolan's adaptation.

I own copies of 3 more Priest books, which I've already owned for over 3 years: The Dream Archipelago (1999), The Separation (2002), and The Islanders (2011). I wonder how long before get round to reading these.

Thursday 19 May 2016

Paradise Lost (Again)

I've been re-reading 'Paradise Lost', because it's damned good. I felt like writing something about it again, because when I wrote about it two years ago I was still very giddy about how good it is, was still hyper from the discovery that reading a poem could be an immersive cinematic experience, and the thing I wrote back then is very unsatisfying to re-read: my 'ZOMFG I cant tel u how awsum it is' fanboying makes me cringe.

So I started to write about it again, thinking that re-reading it two years on I would be able to do it more justice, perhaps a little calmer, perhaps with some more analysis. For those that don't know: 'Paradise Lost' is a 17th century epic poem by John Milton, which tells 'Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste brought death into the world, and all our woe, with loss of Eden'. It is a retelling of the the War in Heaven and creation myths from Judeo-Christian mythology. And it's so good: one of the greatest works of English literature.

There was going to be more to this. I was going to go through the whole thing in a series of posts, perhaps one for each chapter/book that makes up the epic, discussing the scenes and including a few choice quotes.

But I can't do it. I just fanboy over it too much. I want to quote the whole thing. Here's Satan rising out of a lake of fire in the early pages:

'Forthwith upright he rears from off the pool

His mighty stature; on each hand the flames

Driven backward slope their pointing spires, and rolled

In billows, leave i' the midst a horrid vale.'

And then there's the speeches. And the fight scenes. And the sex scene. And the montages (yes, montages: it's a cinematic poem). It's just so good.

ZOMFG I cant tel u how awsum it is.

So I started to write about it again, thinking that re-reading it two years on I would be able to do it more justice, perhaps a little calmer, perhaps with some more analysis. For those that don't know: 'Paradise Lost' is a 17th century epic poem by John Milton, which tells 'Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste brought death into the world, and all our woe, with loss of Eden'. It is a retelling of the the War in Heaven and creation myths from Judeo-Christian mythology. And it's so good: one of the greatest works of English literature.

There was going to be more to this. I was going to go through the whole thing in a series of posts, perhaps one for each chapter/book that makes up the epic, discussing the scenes and including a few choice quotes.

But I can't do it. I just fanboy over it too much. I want to quote the whole thing. Here's Satan rising out of a lake of fire in the early pages:

'Forthwith upright he rears from off the pool

His mighty stature; on each hand the flames

Driven backward slope their pointing spires, and rolled

In billows, leave i' the midst a horrid vale.'

And then there's the speeches. And the fight scenes. And the sex scene. And the montages (yes, montages: it's a cinematic poem). It's just so good.

ZOMFG I cant tel u how awsum it is.

Best of 2016 (So Far)

My five favourite books of 2016 so far:

'If On A Winter's Night A Traveller' by Italo Calvino is now one of my favourite books of all time, joining the illustrious company of The Picture of Dorian Gray, Star Maker, the Hebrew Bible, and Paradise Lost. A postmodern second-person narrative (You, the Reader, are the protagonist) which explores the acts of reading and writing, and contains ten unfinished novels within it.

'The Revolt of the Angels' by Anatole France. Satirical fantasy that plays with Christian mythology: a Guardian angel in 20th century France spends too much time in a library, studying science, philosophy, and history, which convinces him to join the fallen angels, who have been recast as somewhat comically inept radical left-wing revolutionaries ("we shall carry war into the heavens, where we shall establish a peaceful democracy"). Jokes at the expense of government, hard-left politics, war, religion, and more.

'The Birds' is one of Tarjei Vesaas' two most famous works (the other is 'The Ice Palace'). Vesaas is not well known is the English-speaking world, but is considered one of Norway's greatest writers. The English editions are published by Peter Owen Modern Classics, a family-run independent publisher. So many hipster points for this book. The protagonist is a man with learning difficulties who lives with his sister, and struggles to cope when their situation changes. It's such a beautifully humane story.

'Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come' by Norman Cohn traces the development of apocalyptic faith - the belief in a perfect future where good has triumphed over evil - from the ancient Mesopotamian, Egyptian and Vedic mythologies, through Zoroastrianism to Judaism and Christianity.

'Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind' is one of those popular books that you'll probably hate if you're already knowledgeable about the subject. As it is, history is not my strongest subject, so I only found the early chapters on evolution and 'Out of Africa' migrations intensely irritating (I had covered this subject enough during my degree, so reading these chapters felt like a waste of time). It is, of course, a very brief history: an introduction to human history, focusing on general trends and major developments. As an introduction to the topic, it is exemplary.

'If On A Winter's Night A Traveller' by Italo Calvino is now one of my favourite books of all time, joining the illustrious company of The Picture of Dorian Gray, Star Maker, the Hebrew Bible, and Paradise Lost. A postmodern second-person narrative (You, the Reader, are the protagonist) which explores the acts of reading and writing, and contains ten unfinished novels within it.

'The Revolt of the Angels' by Anatole France. Satirical fantasy that plays with Christian mythology: a Guardian angel in 20th century France spends too much time in a library, studying science, philosophy, and history, which convinces him to join the fallen angels, who have been recast as somewhat comically inept radical left-wing revolutionaries ("we shall carry war into the heavens, where we shall establish a peaceful democracy"). Jokes at the expense of government, hard-left politics, war, religion, and more.

'The Birds' is one of Tarjei Vesaas' two most famous works (the other is 'The Ice Palace'). Vesaas is not well known is the English-speaking world, but is considered one of Norway's greatest writers. The English editions are published by Peter Owen Modern Classics, a family-run independent publisher. So many hipster points for this book. The protagonist is a man with learning difficulties who lives with his sister, and struggles to cope when their situation changes. It's such a beautifully humane story.

'Cosmos, Chaos and the World to Come' by Norman Cohn traces the development of apocalyptic faith - the belief in a perfect future where good has triumphed over evil - from the ancient Mesopotamian, Egyptian and Vedic mythologies, through Zoroastrianism to Judaism and Christianity.

'Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind' is one of those popular books that you'll probably hate if you're already knowledgeable about the subject. As it is, history is not my strongest subject, so I only found the early chapters on evolution and 'Out of Africa' migrations intensely irritating (I had covered this subject enough during my degree, so reading these chapters felt like a waste of time). It is, of course, a very brief history: an introduction to human history, focusing on general trends and major developments. As an introduction to the topic, it is exemplary.

As If Through A Dense Forest

'The pleasures derived from the use of a paper knife are tactile, auditory, visual, and especially mental. Progress in reading is preceded by an act that traverses the material solidity of the book to allow you access to its incorporeal substance. Penetrating among the pages from below, the blade vehemently moves upward, opening a vertical cut in a flowing succession of slashes that one by one strike the fibers and mow them down—with a friendly and cheery crackling the good paper receives that first visitor, who announces countless turns of the pages stirred by the wind or by a gaze—then the horizontal fold, especially if it is double, opposes greater resistance, because it requires an awkward backhand motion—there the sound is one of muffled laceration, with deeper notes. The margin of the pages is jagged, revealing its fibrous texture; a fine shaving—also known as "curl"—is detached from it, as pretty to see as a wave's foam on the beach. Opening a path for yourself, with a sword's blade, in the barrier of pages becomes linked with the thought of how much the word contains and conceals: you cut your way through your reading as if through a dense forest.'

We do not need paper knives any more: the pages of our books come ready separated. I recently purchased a 1901 omnibus edition of 'Sartor Resartus' and 'Heroes & Hero Worship' by Thomas Carlyle. (It is the 2nd oldest book I own: the oldest is an 1896 edition of The Martyrdom of Man by Winwood Reade.) However many people owned this book before myself, in the 115 years of its existence, none of them read 'Sartor Resartus' to the end. (All the pages of 'Heroes & Hero Worship' have been separated.) They gave up at chapter 10, 'Pause', as though they took its title as an imperative and never returned to finish the job. Cutting through a book, unlocking its words, being the first person to read its virgin pages, as though they have been waiting for me for over a century, has been a fun novelty. It also amuses me to have a big kitchen knife on my bedside for this purpose, because who owns a paper knife these days? I quoted Italo Calvino above, because DAT WRITING.

Wednesday 18 May 2016

'The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe' by D.G. Compton

I have not had much luck with my SF Masterworks reading recently. Synners (1991) by Pat Cadigan, The Sea and Summer (1987) by George Turner, Floating Worlds (1976) by Cecelia Holland, and Unquenchable Fire (1988) by Rachel Pollack were all so boring that I gave up on them. Babel-17 (1966) by Samuel R. Delany, A Maze of Death (1970) by Philip K. Dick, The Fountains of Paradise (1979) by Arthur C. Clarke, and Cat's Cradle (1963) by Kurt Vonnegut were each entertaining but to varying degrees disappointing. I have read better books by Clarke, Dick, and Vonnegut.

The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe (1973) by D.G. Compton is the best SF Masterwork I've read in months.

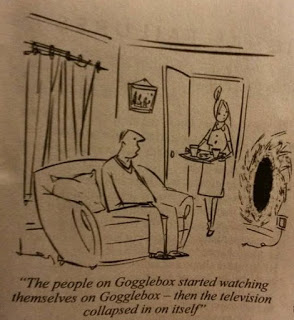

Reality TV is very popular these days. We can, if so inclined, choose to watch real people: competing over performance skills (The X Factor, Britain's Got Talent, etc), being affluent housewives (The Real Housewives of Cheshire, etc), working in a kitchen (Jamie's Kitchen, Kitchen Nightmares, etc), working in a tattoo shop (Miami Ink, etc), driving on icy roads (Ice Road Truckers, etc), coping with teenage pregnancy and motherhood (16 and Pregnant, Teen Mom, etc), buying and selling antiques (Bargain Hunt, etc), being affluent youngsters (Made in Chelsea, etc), going on dates (First Dates, The Undateables, etc), cleaning houses (How Clean Is Your House?, Obsessive Compulsive Cleaners, etc), being poor (Benefits Britain, Benefits Street, Skint, etc), sharing a house (Big Brother), being in an airport and or on a plane (Airport, Airline, etc), buying and selling houses (Location, Location, Location, etc), being in hospital (24 Hours in A&E, etc), losing weight (The Biggest Loser, etc), or coping with medical problems (Embarrassing Bodies, etc). If that's all too exciting for us, we can instead watch people watching TV (Gogglebox).

|

| From Private Eye 1406 |

I don't watch much TV; I don't have a TV license; I use DVDs, Netflix, 4OD, and BBC iPlayer if there's something I really want to watch. I had to use Wikipedia's lists of reality TV shows to research the above paragraph.

Back in the 70s, when Compton was writing The Continuous Katherine Mortenhoe, reality TV was only just appearing with a few experimental shows. These had a powerful effect on the popular imagination of the time, inspiring a range of SF writers, such as Compton.

In Katherine Mortenhoe's world, medical science has cured most illnesses, so most people die of old age or serious injuries (such as car crashes). Terminal illnesses are rare anomalies, and there's money to be made in filming rare anomalies and selling it to the public. Katherine is diagnosed with a terminal illness at the age of 44, giving her only 28 days to live, and must make tough choices about what to do with her remaining days, knowing that her privacy will be destroyed. It's quite a bleak book.

Compton writes well, and - to make a good point about the fake reality of reality TV - switches between third and first person narration: Katherine's story is narrated in the third person, telling us her actions but little of her thoughts; Roddie - 'The Man with the TV Eyes', a reporter with cameras in his eyes - narrates in the first person, giving his thoughts and his interpretation of Katherine's actions. Thus, Katherine's true character, her thoughts and goals, her inner life, are hidden from us: we have to figure it our for ourselves. The reader, like Roddie, like the viewers of reality TV, see only the external reality, missing out on all the inner complexity that makes people who they are. Our eyes may process the same images, but how we interpret them will differ.

'You see, beauty isn't in the eye of the beholder. Neither is compassion, or love, or even common human decency. They're not of the eye, but of the mind behind the eye.'

The story is gripping and well-written. The premise is brilliantly bleak. The main characters are well-rounded and memorable. The anti-TV message is one I can get behind. It is a very good book.

However, the novel's world is rather shallow: there are brief mentions of Privacy Laws (relating to when and where reporters can film), fringies (people who live on benefits on the fringes of society), Computabooks (computer-generated books), and various political protest marches occurring, but it is not explored in depth. We are given no clues as to what country, or how far in the future, the story is set. Beyond the TV Eyes, advanced medical science, and Computabooks, there is little to no mention of technological progress. This all dates the novel: with those few exceptions, our dystopian present looks far more futuristic than Mortenhoe's world. Perhaps the list of reality TV shows above demonstrates that our dystopian present is also more terrifying than Mortenhoe's world...

But this is not a book about a dystopian society, and should not be read as such. It is, and succeeds as, a story about a woman coming to terms with her imminent death, and a man trying to understand her. Recommended.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)